Who's defining sustainability for aquaculture?

More organizations are bringing fish farms into their sustainability goals and initiatives, but many lack clear metrics of success. What does sustainable aquaculture actually mean?

Consumer interest and regulatory pressure have driven a global shift in capital toward more sustainable and transparent business practices.

A 2021 report from The Economist Intelligence Unit and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) showed a 71 percent rise in online searches for sustainable goods across the globe since 2016, while hundreds of public and private entities announced commitments to more environmentally friendly practices at last month’s U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP26).

Seafood is at the core of many of these discussions, sitting at the nexus of ocean conservation, food security, and the climate crisis. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization says that aquaculture will be key to meet an increasing global food demand.

More and more businesses are now looking to aquaculture as a powerful tool in their own sustainability efforts. But these new and ambitious goals lack clear metrics of success: What does sustainable aquaculture actually mean?

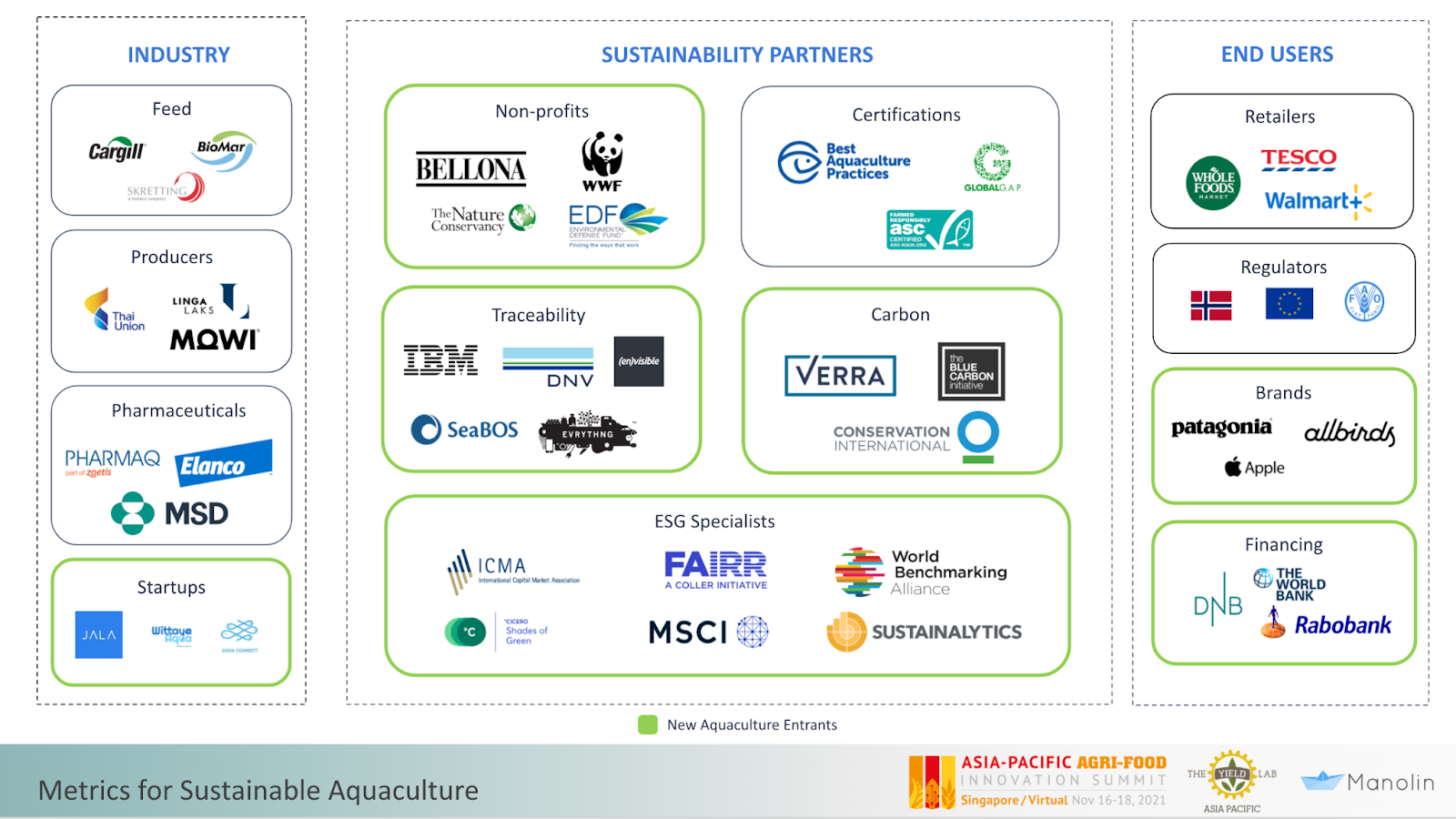

Manolin and ag-tech investment fund The Yield Lab Asia Pacific built a map of those defining the future of aquaculture sustainability for the Asia-Pacific Agri-Food Innovation Summit last month.

Today, 90 percent of marine fish stocks are fully exploited, overexploited, or depleted, and climate change continues to disrupt global supply chains. Aquaculture fills a critical gap in global food supply and demand, providing the majority (52 percent) of the world’s fish for human consumption. It is now the fastest-growing food-production sector. When managed poorly, though, fish farms can be breeding grounds for disease, pollute local ecosystems, and put further strain on wild fish stocks.

The current landscape addresses these issues across a range of categories: environment, animal welfare, traceability, community, and feed. The Global Seafood Alliance built end-to-end certification (BAP) so farmers can communicate safe, responsible, and ethical practices with consumers. BioMar developed more sustainable and nutritious fish feed using fermented microalgae. And Norway-based Lingalaks is developing a floating, closed salmon-farming production unit that aims to reduce or eliminate challenges related to salmon lice, escape of fish, and organic waste.

Recently, new entrants are building a more robust picture of how aquaculture contributes to climate efforts.

The ocean drives global weather systems, distributes heat, stores solar radiation, and is at the core of our atmospheric cycles. It's currently absorbing about a quarter of anthropogenically generated atmospheric carbon. Especially as the final Article 6 rules coming out of COP26 are expected to jump-start a surge of carbon-offset buying, blue carbon frameworks are now bringing aquaculture systems into the conversation. Verra registered its first “blue carbon” conservation project this year, while the Blue Carbon Initiative released guidance for countries to include blue carbon in national emissions reduction commitments (NDCs) in 2020.

Meanwhile, environmental nonprofits – many of which have historically avoided work in aquaculture – are recognizing the importance of building a sustainable aquaculture industry to support, rather than degrade, ocean health.

Environmental advocacy groups are building aquaculture sustainability frameworks, such as the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) Oceans’ new initiative this year to chart a responsible path forward for offshore aquaculture in the United States. They’re also building financial pipelines to boost capital: This year, WWF devoted part of its USD 100 million (EUR 89 million) grant from the Bezos Earth Fund to a global study to validate the carbon sequestration impact of ocean farming. And in 2020, The Nature Conservancy partnered with aquaculture accelerator Hatch Blue to identify companies with the potential to dramatically increase benefits and reduce environmental harm of aquaculture production.

Each of these players has its own particular focus. Looking ahead, better alignment across the industry can amplify impact. For the private sector to fully take advantage of new financial pipelines, the nonprofit space to build impactful partnerships across sectors, and policy to effectively benefit all, sustainable aquaculture needs common metrics and a common definition – one that balances efforts to maximize mutually beneficial outcomes.

This piece originally published on SeafoodSource.com in December 2021.

For more data, content, and insights, subscribe to Manolin’s newsletter. Interested in working with us to help fuel aquaculture sustainability? Get in touch here.